Hamza* is bright, kind, and quick to laugh. His excitement unfolds quickly as he explains the way he has experienced the Keystone Project turning strangers from different backgrounds into friends with great shared trust.

He initially began participating in Keystone because of the opportunity to exercise with other men. Eventually, in addition to the exercise, the unique opportunity to build relationships among participants continued to compel him to come. After completing the program, Hamza interviewed to become a coach and now leads his own sessions.

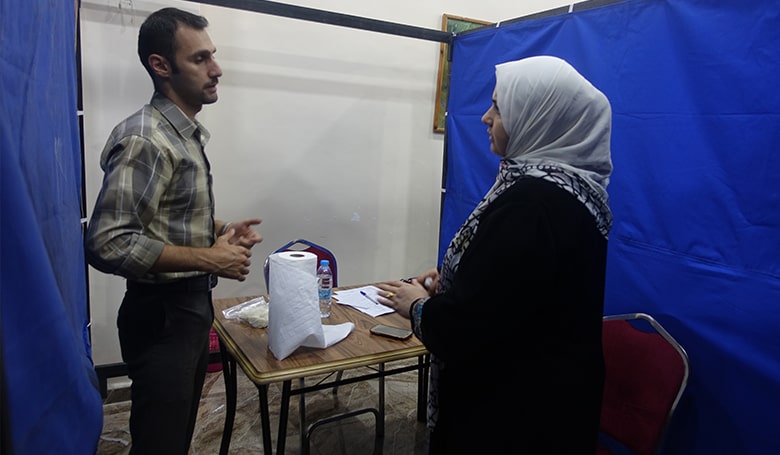

Hamza opens sessions with a time of sharing and learning before the men get moving in the workout class. In accordance with the session topic, Hamza encourages participants to share “even their griefs” with each other. This openness helps participants engage with and support one another, “we need each other,” he says earnestly.

“Everyone has faced different challenges in their lives,” Hamza states regarding the participants. “If one of us cannot walk through one of these challenges, a [fellow] participant can help him overcome this challenge.” Because the men take risks to open up, Hamza gladly remarks, “After just three months together, we began to have a brotherly connection to each other.”

“Before,” shares Hamza, “my relationships were limited. Now, in the project, my relationships grow and grow.”

Hamza also loves the way these relationships extend beyond their time in the sessions. “As a trainer, I was able to help [the participants] in many ways, both outside and inside the Organization,” Hamza explains. For example, he speaks of several participants who were unable to find work, many of them Syrian refugees. He talks about going down to the marketplace, or Souq, with them and walking from shop to shop, looking for job openings alongside them as they went, shoulder to shoulder.

This type of relational trust built between participants who are often not from the same family, tribe, or background, is no easy task. While it wouldn’t be obvious now, Hamza explains that the first gathering was difficult for him as a coach, “There was tension and stress… I was a new person to them, and they were new to me. Because of this, we would always start by joking around, and when I began the first lesson, I would open by giving a personal example.” Hamza discovered that his openness to share his own faults and challenges encouraged the group to join in.

“We would begin earning one another’s trust,” he explains.

During one lesson, he recalls asking the group, “What is the worst habit you have in your life?” His question was met by silence; no one wanted to open up and admit anything. Finally, he responded by saying about himself, “I’m easily angered! When I come home and there’s no food, for example, I get upset! It’s normal. Every one of us has something like this.” He goes on to clarify by saying, “I give them an example of myself in the beginning. Then trust grows as we plant it, and someone responds with, ‘Me too. I’m easily angered too.’ Then we talk and find solutions to address how we respond to anger so that it doesn’t affect our families.” He explains that these changes become “rooted,” especially as they are done in the community.

Hamza relates the message of friendship that is sown and grown in the project to the example of one man who cannot stand on one leg and remain balanced. Hamza illustrates how with a fellow participant helping him, he can stand. He explains the same idea by giving the example of a man who could not perform push-ups during the session, but with a friend supporting him, working with him towards the goal, shoulder to shoulder, he could do it.

This picture illustrates the typical pattern within the Keystone sessions. There is a depth of solidarity relationally, emotionally, and physically amongst these men. This solidarity expresses the power of living “shoulder to shoulder” as they pursue health and community thriving.

*Name changed